In the 1840s, Charles Babbage designed a mechanical calculator with 8,000 parts to compute error-free mathematical tables. The project was too ambitious for Victorian-era resources and was never completed. Over 150 years later, the Science Museum in London built it to his exact specifications — and it worked perfectly.

Charles Babbage Designed a Mechanical Computer in the 1840s That Was Too Ambitious for Its Time — 150 Years Later, Engineers Built It and It Worked Perfectly

In the 1840s, English mathematician Charles Babbage designed something extraordinary: a mechanical calculator with 8,000 precision-engineered parts that could compute mathematical tables automatically, eliminating the human errors that plagued everything from astronomy to sea navigation.

Difference Engine No. 2

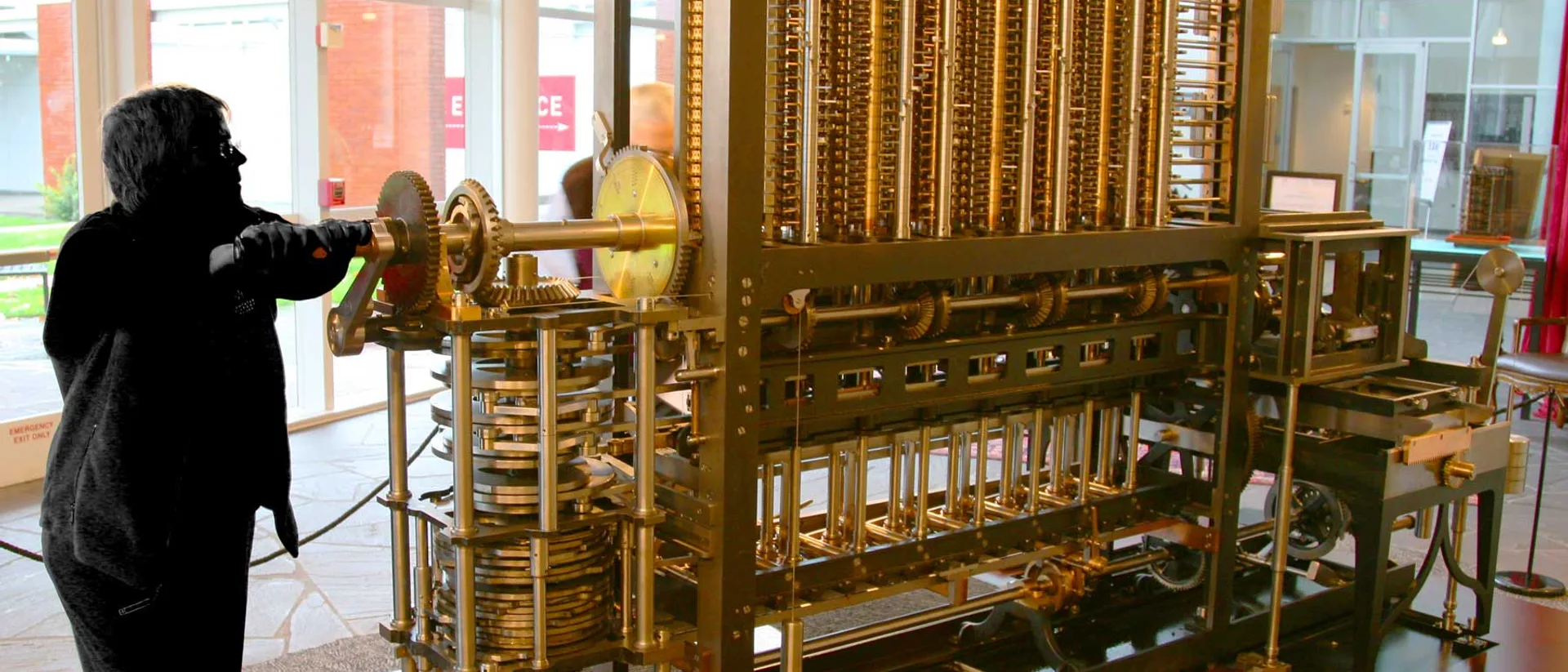

Babbage called it the Difference Engine No. 2 — a refined version of his earlier, even more ambitious design from 1822 (which would have required 25,000 parts). The machine used the mathematical method of finite differences to calculate polynomial functions, then automatically printed the results — all through an intricate system of brass gears, levers, and cams.

The stakes were real. Mathematical tables computed by hand were full of errors. Navigational tables with mistakes could cause ships to miscalculate their position, leading to groundings and wrecks. As astronomer John Herschel put it: "An undetected error in a logarithmic table is like a sunken rock at sea yet undiscovered, upon which it is impossible to say what wrecks may have taken place."

Too Ambitious for Its Time

Despite the clear need, the project collapsed. The British government had already sunk over £17,000 (equivalent to millions today) into Babbage's earlier engine before losing patience. Funding dried up, and bitter disputes between Babbage and his chief engineer Joseph Clement made progress impossible.

Babbage completed the designs but never saw his machine built. He died in 1871, widely regarded as a brilliant but impractical visionary.

150 Years Later

Starting in 1985, a team at the Science Museum in London set out to answer a question that had lingered for over a century: would Babbage's design actually work?

They built the calculating section first, completing it in 1991 for the bicentenary of Babbage's birth. The printing mechanism followed in 2002. Crucially, they used only manufacturing tolerances that would have been available in the Victorian era.

The result? The machine worked perfectly — computing results to 31 digits of accuracy. Babbage had been right all along. The technology of his time could have built it. The world just didn't let him finish.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Babbage's Difference Engine designed to do?

Why was the Difference Engine never completed in Babbage's lifetime?

When was the Difference Engine finally built?

What is the difference between Difference Engine No. 1 and No. 2?

Verified Fact

Verified against multiple authoritative sources. Babbage designed Difference Engine No. 2 between 1846-1849 (not 1822 — that was Difference Engine No. 1 with ~25,000 parts). DE No. 2 has ~8,000 parts split between calculating section and printing mechanism. Primary purpose was computing error-free mathematical tables (navigational, logarithmic, astronomical). Project abandoned due to funding disputes with the British government and personality clashes with engineer Joseph Clement — NOT because Victorian technology couldn't build it. Science Museum London built the calculating section 1985-1991 (completed for Babbage's bicentenary), printing mechanism added 2002. They deliberately used only tolerances achievable in Babbage's era. Machine worked perfectly, proving the design was sound. Corroborated by Science Museum official documentation, Computer History Museum, IEEE Spectrum, Britannica, and Wikipedia.

Science Museum