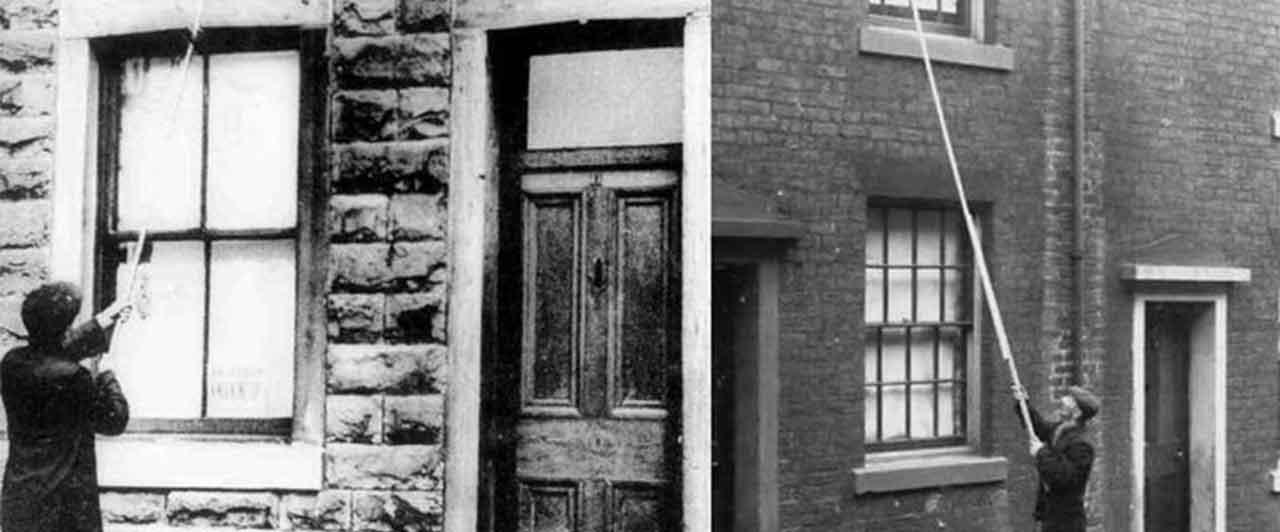

Until the 1920s, there was a profession called 'knocker-up', which involved going from client to client and tapping on their windows (or banging on their doors) with long sticks until they woke up.

Knocker-Uppers: The Human Alarm Clocks of Industrial Britain

Before smartphones and digital alarms, before electric buzzers, even before affordable mechanical clocks, there was a person with a stick standing outside your window at 4 a.m. The knocker-up was Industrial Britain's solution to a very modern problem: how do you get thousands of factory workers out of bed when shifts start before sunrise?

The profession emerged in the late 18th century as textile mills and factories transformed sleepy towns into industrial powerhouses. Workers needed to clock in at precise times or risk losing their jobs, but reliable alarm clocks wouldn't become affordable household items for decades. Enter the knocker-up, armed with a long bamboo pole and an intimate knowledge of their neighborhood's sleep schedules.

The Tools of the Trade

Knocker-uppers used surprisingly varied techniques. The most common was a long, lightweight stick—often bamboo—to tap on upper-floor windows. For ground-floor customers, a heavier baton worked for door-banging. Some knocker-uppers got creative: a famous 1929 photograph shows Mary Smith of East London using a pea-shooter to ping dried peas at bedroom windows, a method that was loud enough to wake the sleeper but gentle enough not to shatter glass.

The job required precision timing and remarkable memory. A single knocker-up might serve dozens of clients, each requiring a wake-up call at a different time. They'd make their rounds in the pre-dawn darkness, waiting at each window until they saw movement or heard confirmation before moving on.

Who Did the Knocking?

Knocker-uppers came from all walks of life. Many were elderly men and women supplementing meager incomes—the job paid just a few pence per client per week. Some were police constables making extra money during their rounds. Interestingly, many were older women who'd aged out of factory work but still needed income.

This raises the obvious question: who woke up the knocker-uppers? Most were naturally early risers or held other jobs that kept them on unusual schedules. Some were insomniacs who turned their affliction into a business opportunity.

The Long Goodbye

The fact states the profession lasted "until the 1920s," which is both true and an understatement. While knocker-uppers were indeed common through the 1920s, the profession didn't die overnight. In some industrial pockets of England, knocker-uppers were still working into the early 1970s, particularly in areas where shift work remained common and older residents either couldn't afford alarm clocks or simply preferred the human touch.

What finally killed the knocker-up wasn't just technology—it was the mass production of affordable, reliable alarm clocks after World War II. By the 1950s, wind-up clocks had become so cheap and dependable that paying someone to tap on your window seemed quaint at best, unnecessary at worst.

Today, the knocker-up lives on as a curious footnote in labor history, a reminder that every modern convenience once required a human workaround. The profession also highlights something we often forget: timekeeping itself is a relatively modern obsession, one that literally required creating new jobs to enforce it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did knocker-uppers use to wake people up?

Who woke up the knocker-uppers?

When did the knocker-up profession end?

How much did knocker-uppers get paid?

Were knocker-uppers only in Britain?

Verified Fact

The profession existed from the Industrial Revolution through the 1920s and beyond (into the 1970s in some areas). The methods described—tapping windows with long sticks and banging on doors—are accurate. While the fact states 'until the 1920s,' the profession actually persisted longer in some areas, but the 1920s marked the beginning of its general decline.