People in parts of Western China put salt in their tea instead of sugar.

Why Salt Goes in Tea Across Western China

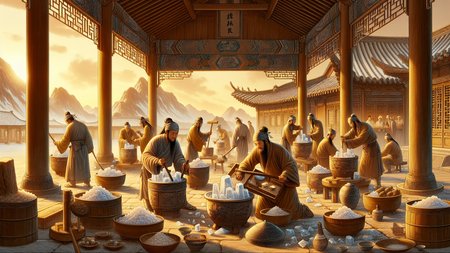

If someone offered you a cup of tea with salt instead of sugar, you'd probably think they were pranking you. But across Western China—from the Tibetan Plateau to Xinjiang—millions of people drink salted tea every single day. And they've been doing it for centuries.

This isn't some quirky food trend. It's survival, culture, and hospitality all steeped into one cup.

The Butter Tea of Tibet

In Tibet, the traditional drink is po cha (butter tea)—a thick, savory blend of black tea, yak butter, and salt. Tibetans don't sip it casually. They drink up to 60 small cups per day, with surveys showing 73.9% of Tibetans prefer it over any other tea. For many, it's consumed at least three times daily, sometimes a dozen.

The recipe is simple but specific: boil tea leaves (often compressed brick tea), churn in yak butter and salt, sometimes add roasted barley flour. The result? A creamy, salty, high-calorie drink that tastes nothing like the tea you know.

Why salt and butter? At high altitudes, your body burns calories fast just trying to stay warm and oxygenated. Butter tea is dense with fat and sodium—exactly what you need to fight fatigue, cold, and altitude sickness. It's fuel in a cup.

Xinjiang's Salted Milk Tea

Head northwest to Xinjiang, and you'll find another salted tea tradition among the Kazakh, Uyghur, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz ethnic groups. Here, it's salted milk tea—black brick tea boiled with cow or goat milk and seasoned with salt.

The preparation varies slightly by group, but the philosophy is the same: "It is better to have no food for a day than tea for a day." A classic Xinjiang breakfast pairs a bowl of this salty tea with a lamb-filled baozi, offering warmth and energy to start the day.

Like in Tibet, the harsh climate drives the practice. Cold winters, rugged terrain, and nomadic lifestyles make salted tea a practical necessity—not just a cultural quirk.

Still Going Strong Today

This isn't a dying tradition kept alive by grandmothers. Modern Tibetans and Xinjiang residents still drink salted tea daily. While some urban dwellers now use cow butter instead of pricey yak butter, or tea bags instead of brick tea, the core practice endures.

Butter tea is served at Tibetan weddings, funerals, and everything in between. In recent years, it's even appeared on menus in Kathmandu and Pokhara cafes, introducing curious tourists to the Himalayan staple.

What Does It Taste Like?

For first-timers, salted tea is weird. It doesn't taste like tea—it tastes like a savory broth. Some describe butter tea as "soupy," with an oily texture and a flavor that's earthy, salty, and rich. It's polarizing. You either love it or spend the rest of the day trying to forget it.

But for the millions who grew up with it, salted tea is comfort. It's what your grandmother poured when you visited. It's what kept your ancestors alive on frozen mountain passes. It's home.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do Tibetans put salt in their tea?

What is Tibetan butter tea made of?

Do people still drink salted tea in China today?

What does salted butter tea taste like?

Which ethnic groups in China drink salted tea?

Verified Fact

Confirmed that salted tea is still widely consumed today in Western China, particularly in Tibet (butter tea/po cha) and Xinjiang (Kazakh/Uyghur milk tea). Tibetans drink up to 60 small cups daily, and 73.9% prefer butter tea. The practice remains essential to daily life and culture.