In the 1770s, Swiss watchmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz built three incredibly sophisticated automata, including 'The Writer'—a mechanical boy that could write custom messages up to 40 characters long using a quill pen, all programmable by rearranging cams on a wheel.

The 250-Year-Old Robot That Could Write

In a workshop in Switzerland during the 1770s, a watchmaker named Pierre Jaquet-Droz was building something that wouldn't look out of place in a sci-fi film. His creation: a mechanical child that could dip a quill in ink, write custom messages, and even move its eyes to follow its own handwriting.

This wasn't magic. It was engineering so precise it still works today.

The Uncanny Trio

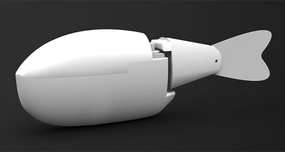

Jaquet-Droz didn't stop at one automaton. He built three: The Writer, The Musician, and The Draughtsman. Each was a marvel of miniaturization, containing thousands of hand-crafted parts smaller than a fingernail.

The Writer remains the most famous. This doll-sized figure sits at a tiny desk, holds a real goose-feather quill, and can write any text up to 40 characters. Its eyes track the words as they form. Its chest rises and falls as if breathing. When it finishes a word, it lifts the pen and moves to the next space with mechanical grace.

Programmable—In 1774

Here's where it gets eerie: The Writer was programmable. A wheel inside the automaton contains 40 cams, each corresponding to a letter position. By rearranging these cams, you could make the mechanical boy write anything you wanted.

This wasn't just a party trick. It was the conceptual ancestor of computer programming, created two centuries before Alan Turing was born.

- 6,000 parts make up The Writer's mechanism

- 40 characters can be programmed per message

- 250+ years and it still functions perfectly

Why Build Mechanical Children?

Jaquet-Droz wasn't just an artist—he was a salesman. These automata were advertisements for his watchmaking prowess. If he could build a robot that writes, imagine what he could do with your pocket watch.

The strategy worked brilliantly. Kings and emperors clamored for his timepieces. He became one of the wealthiest watchmakers in Europe.

But there was something darker lurking beneath the wonder. Audiences in the 18th century weren't just amazed—they were unsettled. The Church questioned whether creating such lifelike machines bordered on playing God. Some whispered about sorcery.

Still Alive After 250 Years

Today, all three automata reside in the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. They still work. Curators periodically wind them up for demonstrations, and The Writer still puts quill to paper with the same fluid motions it performed for Marie Antoinette.

There's something haunting about watching a machine older than the United States write a message in perfect cursive. It's a reminder that our obsession with artificial beings isn't new. We've been trying to create mechanical life for centuries.

Jaquet-Droz just got closer than anyone thought possible.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who invented the first writing robot?

How does the Jaquet-Droz Writer automaton work?

Where can you see the Jaquet-Droz automata today?

Why did Pierre Jaquet-Droz build automata?

Is the Jaquet-Droz Writer the oldest robot?

Verified Fact

Corrected: Pierre Jaquet-Droz created three automata (not just one), and while 'The Writer' could indeed write, the mechanism was programmable via a cam wheel, not truly 'interchangeable parts' in the modern sense. Clarified the fact.