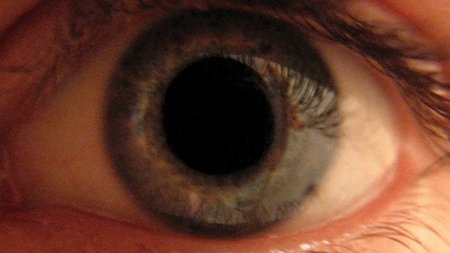

Optical illusions occur when what the eyes see conflicts with what the brain expects.

Why Your Brain Falls for Optical Illusions

Your brain is a prediction machine. Every second, it's making educated guesses about what you're seeing, often filling in gaps before your eyes can catch up. Optical illusions exploit this system, creating scenarios where your brain's expectations clash spectacularly with reality.

When you look at something, your eyes send raw visual data to your brain. But your brain doesn't just passively receive this information—it actively interprets it based on past experiences, context clues, and built-in assumptions about how the world works. Most of the time, this system works flawlessly. But optical illusions reveal the cracks in the code.

The Classic Tricks

Take the famous Müller-Lyer illusion: two lines of identical length, one with arrows pointing inward, one with arrows pointing outward. The line with outward arrows looks longer, even when you measure them. Your brain interprets the outward arrows as a corner receding into the distance, so it assumes that line must be longer to create the same retinal image.

Or consider afterimages—stare at a bright red square for 30 seconds, then look at a white wall. You'll see a green square that isn't there. Your color-detecting cells got exhausted, and their opposing color receptors are now firing unopposed.

Why We're So Easy to Fool

These perceptual glitches happen because vision is about efficiency, not perfection. Your brain evolved to make split-second decisions in the real world, where lighting is consistent, objects are solid, and depth cues are reliable. Illusions present impossible scenarios—contradictory depth information, impossible geometries, colors that shouldn't exist—and your brain does its best with bad data.

The fascinating part? Even when you know it's an illusion, you still see it. You can't unsee the Müller-Lyer effect. You can't force the famous rabbit-duck drawing to stop flipping between interpretations. Your conscious mind knows the truth, but your visual processing system is hardwired to interpret patterns in specific ways.

What Illusions Teach Us

Optical illusions aren't just party tricks—they're windows into how perception actually works. Neuroscientists use them to map which brain regions handle specific visual tasks, how quickly processing happens, and where conscious awareness begins. They reveal that what you "see" is less like a camera recording and more like a constructed simulation, built in real-time from incomplete information.

So next time an illusion fools you, don't feel bad. Your brain is doing exactly what it evolved to do: making the best guess possible with the information available. It just happens to be a guess you can trick.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do optical illusions trick your brain?

Can you train yourself to not see optical illusions?

What is the most famous optical illusion?

What do optical illusions teach us about vision?

Why do some people see optical illusions differently?

Verified Fact

Fact is accurate - optical illusions do occur when visual perception conflicts with brain's expectations