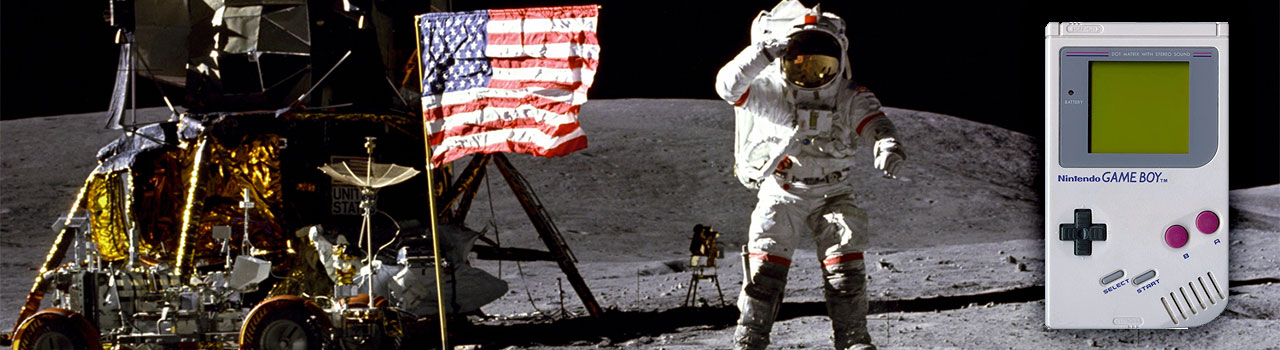

The technology of a single Game Boy exceeds all the computing power that was used to put the first man on moon in 1969.

Game Boy vs. Moon Landing: Tech Power Revealed

It sounds like science fiction, or perhaps a tall tale spun by a nostalgic gamer: a handheld console, designed for simple entertainment, possessing more computational prowess than the very machines that guided humanity to the Moon. Yet, the astonishing truth is that a single Nintendo Game Boy, first released in 1989, indeed surpassed the raw computing power of the sophisticated systems that powered the historic Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

This mind-bending comparison isn't meant to diminish the monumental achievement of the Apollo program. Instead, it serves as a powerful testament to the incredible, relentless march of technological progress in just two short decades.

The Computing Heart of Apollo

In 1969, the Apollo program relied on the cutting-edge Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC). This revolutionary device was the digital brain of both the command module and the lunar module. It was responsible for critical functions like navigation, spacecraft attitude control, and engine firings.

The AGC was an engineering marvel for its time. It pioneered the use of integrated circuits, a concept that would later become fundamental to all modern electronics. Despite its crucial role, its specifications were modest by today's standards. The AGC operated at a clock speed of just 2.048 MHz.

Memory was also extremely limited. It featured approximately 2 kilobytes (KB) of RAM for temporary data storage and about 72 KB of ROM (Read-Only Memory) for storing essential programs and mission data. To achieve complex tasks, programmers had to write highly optimized code, performing feats of digital alchemy with every byte.

Enter the Handheld Revolution: Game Boy

Two decades later, Nintendo unleashed the Game Boy onto the world. This iconic grey brick, powered by four AA batteries, brought portable gaming to the masses. Its primary purpose was entertainment, allowing players to enjoy titles like Tetris and Super Mario Land anywhere.

Beneath its simple facade, the Game Boy housed technology that dwarfed the AGC in several key metrics. Its custom 8-bit CPU ran at a brisk 4.19 MHz, more than double the clock speed of the AGC. This meant it could execute instructions at a significantly faster rate.

The Game Boy also boasted more accessible memory. It came equipped with 8 KB of internal RAM, plus an additional 8 KB of video RAM dedicated to graphics processing. Game cartridges, which served as the console's ROM, offered capacities ranging from 32 KB up to over 1 megabyte (MB) for later titles. This allowed for far more complex games and graphics than the AGC's fixed programming.

Why Such a Leap in Power?

The vast difference in computing power between the AGC and the Game Boy can be attributed to several factors:

- Moore's Law: This observation, made by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, states that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. Between 1969 and 1989, two decades of exponential growth fundamentally changed what was possible.

- Miniaturization: Advancements in manufacturing allowed for smaller, more efficient, and more powerful components. What required entire racks of circuitry in 1969 could fit onto a single chip in 1989.

- Purpose-Built Design: The AGC was designed for extreme reliability in a hostile environment, with strict power and weight constraints. Its primary goal was mission success, not raw processing speed for complex graphics. The Game Boy, while still robust, was built for mass production and entertainment, benefiting from cheaper, faster components.

- Cost Reduction: As technology matured, the cost per transistor plummeted. This made advanced computing power accessible in consumer devices like the Game Boy, which retailed for around $89.99 upon launch.

A Testament to Progress

The comparison between the Apollo Guidance Computer and the Nintendo Game Boy offers a fascinating glimpse into the rapid evolution of technology. Both devices were groundbreaking in their respective eras, achieving incredible feats within their technological constraints.

The AGC's limited resources underscore the ingenuity of the engineers and programmers who landed humans on the Moon. The Game Boy, on the other hand, illustrates how quickly computational power democratized, bringing capabilities once reserved for national space programs into the palm of every child's hand. It’s a powerful reminder that yesterday’s impossible is often just a stepping stone to tomorrow’s everyday.