The first digital camera was invented at Kodak in 1975. They buried the project to protect their film business, bankrupting the company decades later.

The Future in Their Hands: The Digital Camera Kodak Buried

The first digital camera was invented at Kodak in 1975. In a stunning act of corporate self-sabotage, the company buried the project to protect its lucrative film business, a decision that would bankrupt it decades later.

The Clunky Box That Saw Tomorrow

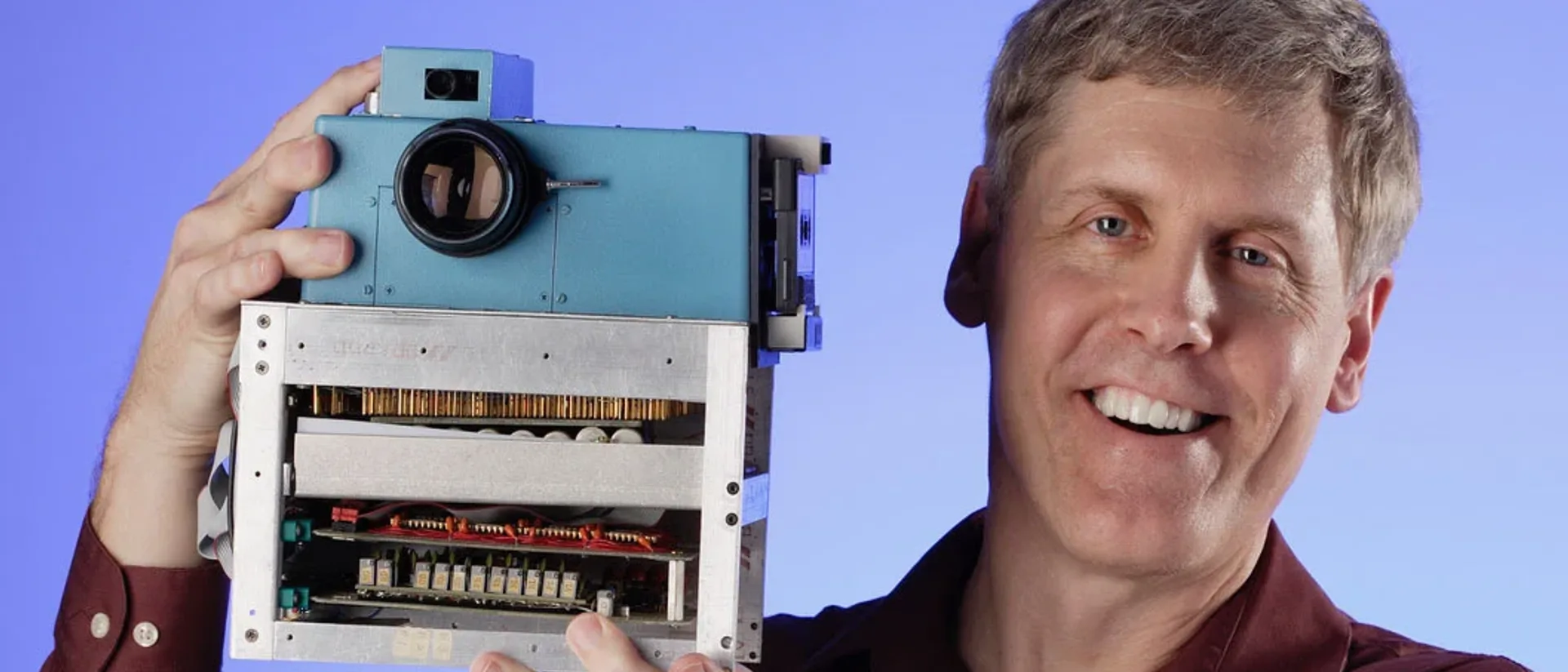

In a back lab at Kodak's Rochester headquarters, a young engineer named Steve Sasson was handed a curious assignment: see if a new type of sensor, called a charge-coupled device (CCD), had any practical use. Sasson and his technician, Jim Schueckler, scavenged parts from other projects—a Super 8 movie camera lens, a portable cassette tape recorder, and 16 nickel-cadmium batteries. The result was a toaster-sized, 8-pound monstrosity that captured a blurry, black-and-white image.

It took 23 seconds to record a single 100-by-100-pixel photo onto the cassette tape. To view it, you had to pop the tape into a custom playback device that displayed it on a standard television. "It was a camera that didn't use any film," Sasson later recalled, "and took pictures that you couldn't print." To the film-centric executives, it was a fascinating but utterly useless toy.

A Future Too Threatening to Embrace

When Sasson demonstrated his invention to various layers of Kodak management, the reaction was a mix of bewilderment and concern. He remembers one executive asking, "But how do you store the images?" Sasson pointed to the cassette tape. "On the tape," he said. The room fell silent. The concept was so alien it was incomprehensible.

The real resistance, however, wasn't technical—it was financial. Kodak's entire empire, from factories to chemistry to paper mills, was built on the "silver-halide" ecosystem of film. Digital photography promised a world without film, without chemicals, without the very products that paid everyone's salary. One manager famously told Sasson, "That's cute—but don't tell anyone about it." The invention was filed for a patent and then quietly locked away.

The Fatal Cost of Protecting the Past

For the next two decades, Kodak treated digital technology as a defensive patent portfolio, not a roadmap to the future. They poured billions into improving film, convinced consumers would always prefer its "quality." Meanwhile, other companies, unburdened by a legacy business to protect, began to innovate.

When digital cameras finally exploded in the 1990s, Kodak was playing catch-up. They actually became a major seller of early digital cameras, but the profit margins were a fraction of film's. The company's core revenue engine had been obliterated by the very technology it invented. In 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy, a fallen giant brought low by its inability to imagine a future different from its past.

An Enduring Lesson in Innovation

Today, Steve Sasson's prototype sits in the Smithsonian. The story of Kodak's digital camera is not just a tale of corporate failure; it's a powerful parable about the courage innovation demands. True vision isn't just about inventing the future—it's about having the bravery to embrace it, even when it means dismantling your own success.

It reminds us that the greatest threat to any established leader is often not the competition, but a stubborn allegiance to the way things have always been. The next revolution might already be in your lab, waiting for someone with the foresight to set it free.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who invented the first digital camera at Kodak?

Why did Kodak not release the first digital camera?

What were the specs of the first digital camera?

Did Kodak ever make digital cameras?

Verified Fact

Well-documented by Steve Sasson's patents, interviews, and multiple historical accounts. Kodak's 2012 bankruptcy filing is a matter of public record.

View sourceRelated Topics

More from Technology & Innovation